A team of Greek researchers has confirmed that bones found in a two-chambered royal tomb at Vergina, a town some 100 miles away from Amphipolis's mysterious burial mound, indeed belong to the Macedonian King Philip II, Alexander the Great's father.

The anthropological investigation examined 350 bones and fragments found in two larnakes, or caskets, of the tomb. It uncovered pathologies, activity markers and trauma that helped identify the tomb's occupants.

Along with the cremated remains of Philip II, the burial, commonly known as Tomb II, also contained the bones of a woman warrior, possibly the daughter of the Skythian King Athea, Theodore Antikas, head of the Art-Anthropological research team of the Vergina excavation, told Discovery News.

The findings will be announced on Friday at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Accompanied by 3,000 digital color photographs and supported by X-ray computed tomography, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray fluorescence, the research aims to settle a decades-old debate over the cremated skeleton.

Scholars have argued over those bones ever since Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos discovered the tomb in 1977-78. He excavated a large mound -- the Great Tumulus -- at Vergina on the advice of the English classicist Nicholas Hammond.

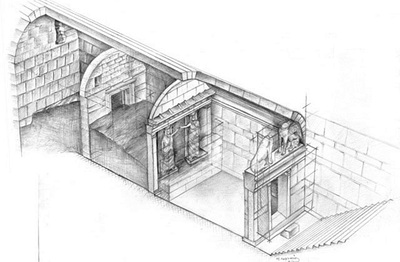

Among the monuments found within the tumulus were three tombs. One, called Tomb I, had been looted, but contained a stunning wall painting of the Rape of Persephone, along with fragmentary human remains.

Tomb II remained undisturbed and contained the almost complete cremated remains of a male skeleton in the main chamber and the cremated remains of a female in the antechamber. Grave goods included silver and bronze vessels, gold wreaths, weapons, armor and two gold larnakes.

Tomb III was also found unlooted, with a silver funerary urn that contained the bones of a young male, and a number of silver vessels and ivory reliefs.

Most of the scholarly debate concentrated on the occupants of Tomb II, with experts arguing that the occupants were either Philip II and Cleopatra or Meda, both his wives, or Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother, who assumed the throne after Alexander's death, with his wife Eurydice.

King Philip II was a powerful fourth-century B.C. military ruler from the Greek kingdom of Macedon who gained control of Greece and the Balkan peninsula through tactful use of warfare, diplomacy, and marriage alliances (the Macedonians practiced polygamy).

His efforts -- he reformed the Macedonian army and proposed the invasion of Persia -- later provided the basis for the achievements of his son and successor Alexander the Great, who went on to conquer most of the known world.

The overlord of an empire stretching from Greece and Egypt eastward across Asia to India, Alexander died in Babylon, now in central Iraq, in June of 323 B.C. — just before his 33rd birthday.

His elusive tomb is one of the great unsolved mysteries of the ancient world.

Analyzed by Antikas' team since 2009, the male and female bones in Philip II's tomb have revealed peculiarities not previously seen or recorded.

"The individual suffered from frontal and maxillary sinusitis that might have been caused by an old facial trauma," Antikas said.

Such trauma could be related to an arrow that hit and blinded Philip II's right eye at the siege of Methone in 354 B.C. The Macedonian king survived and ruled for another 18 years before he was assassinated at the celebration of his daughter's wedding.

The anthropologists found further bone evidence to support the identification with Philip II, who being a warrior, suffered many wounds, as historical accounts testify.

"He had signs of chronic pathology on the visceral surface of several low thoracic ribs, indicating pleuritis," Antikas said.

He noted that the pathology may have been the effect of Philip's trauma when his right clavicle was shattered with a lance in 345 or 344 B.C.

The anthropological investigation examined 350 bones and fragments found in two larnakes, or caskets, of the tomb. It uncovered pathologies, activity markers and trauma that helped identify the tomb's occupants.

Along with the cremated remains of Philip II, the burial, commonly known as Tomb II, also contained the bones of a woman warrior, possibly the daughter of the Skythian King Athea, Theodore Antikas, head of the Art-Anthropological research team of the Vergina excavation, told Discovery News.

The findings will be announced on Friday at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Accompanied by 3,000 digital color photographs and supported by X-ray computed tomography, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray fluorescence, the research aims to settle a decades-old debate over the cremated skeleton.

Scholars have argued over those bones ever since Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos discovered the tomb in 1977-78. He excavated a large mound -- the Great Tumulus -- at Vergina on the advice of the English classicist Nicholas Hammond.

Among the monuments found within the tumulus were three tombs. One, called Tomb I, had been looted, but contained a stunning wall painting of the Rape of Persephone, along with fragmentary human remains.

Tomb II remained undisturbed and contained the almost complete cremated remains of a male skeleton in the main chamber and the cremated remains of a female in the antechamber. Grave goods included silver and bronze vessels, gold wreaths, weapons, armor and two gold larnakes.

Tomb III was also found unlooted, with a silver funerary urn that contained the bones of a young male, and a number of silver vessels and ivory reliefs.

Most of the scholarly debate concentrated on the occupants of Tomb II, with experts arguing that the occupants were either Philip II and Cleopatra or Meda, both his wives, or Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother, who assumed the throne after Alexander's death, with his wife Eurydice.

King Philip II was a powerful fourth-century B.C. military ruler from the Greek kingdom of Macedon who gained control of Greece and the Balkan peninsula through tactful use of warfare, diplomacy, and marriage alliances (the Macedonians practiced polygamy).

His efforts -- he reformed the Macedonian army and proposed the invasion of Persia -- later provided the basis for the achievements of his son and successor Alexander the Great, who went on to conquer most of the known world.

The overlord of an empire stretching from Greece and Egypt eastward across Asia to India, Alexander died in Babylon, now in central Iraq, in June of 323 B.C. — just before his 33rd birthday.

His elusive tomb is one of the great unsolved mysteries of the ancient world.

Analyzed by Antikas' team since 2009, the male and female bones in Philip II's tomb have revealed peculiarities not previously seen or recorded.

"The individual suffered from frontal and maxillary sinusitis that might have been caused by an old facial trauma," Antikas said.

Such trauma could be related to an arrow that hit and blinded Philip II's right eye at the siege of Methone in 354 B.C. The Macedonian king survived and ruled for another 18 years before he was assassinated at the celebration of his daughter's wedding.

The anthropologists found further bone evidence to support the identification with Philip II, who being a warrior, suffered many wounds, as historical accounts testify.

"He had signs of chronic pathology on the visceral surface of several low thoracic ribs, indicating pleuritis," Antikas said.

He noted that the pathology may have been the effect of Philip's trauma when his right clavicle was shattered with a lance in 345 or 344 B.C.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed